: A geography teacher teaches people how to deal with sand and survive in a harsh desert.

Twenty-year-old Maria Nikiforovna Naryshkina, the daughter of a teacher, “hailing from the sandy town of the Astrakhan province” looked like a healthy young man “with strong muscles and firm legs”. Naryshkina owed her health not only to good heredity, but also to the fact that her father protected her from the horrors of the Civil War.

Since childhood, Maria was fond of geography. At sixteen, her father took her to Astrakhan to take pedagogical courses. Maria studied at the course for four years, during which her femininity, consciousness blossomed and her attitude to life was determined.

They distributed Maria Nikiforovna as a teacher in the remote village of Khoshutovo, which was located "on the border with the dead Central Asian desert." On her way to the village, Mary first saw a sandstorm.

The village of Khoshutovo, where Naryshkina reached on the third day, was completely covered with sand. Every day the peasants engaged in hard and almost unnecessary work - they cleared the village of sand, but the cleared places were again filled up. The villagers were plunged "into silent poverty and humble despair."

A tired, hungry peasant many times fussed, worked wildly, but the desert forces broke him, and he lost heart, expecting either someone's miraculous help or resettlement in the wet northern lands.

Maria Nikiforovna settled in the room at the school, discharged everything necessary from the city, and began teaching. The disciples went malfunctioning - then five will come, then all twenty. With the onset of a harsh winter, the school was completely empty. “The peasants were mourned by poverty,” they ran out of bread. By the New Year, two of Naryshkina's students died.

The strong nature of Maria Nikiforovna “began to get lost and fade” - she did not know what to do in this village. It was impossible to teach hungry and sick children, and the peasants were indifferent to the school - it was too far from the "local peasant business."

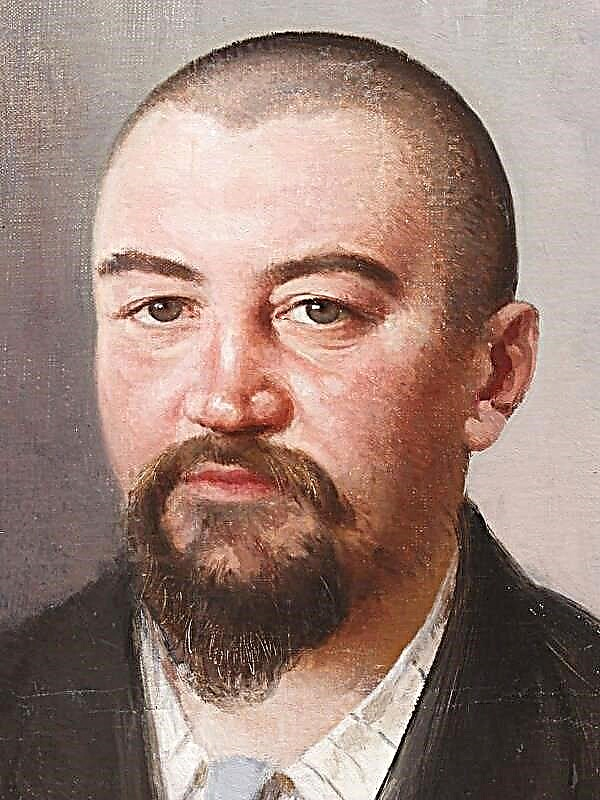

The young teacher came up with the idea that people should be taught how to deal with sand. With this idea, she went to the department of public education, where she was treated sympathetically, but was not given a special teacher, she was only provided with books and "she was advised to teach the sandwork herself."

Having returned, Naryshkina with great difficulty persuaded the peasants "to arrange voluntary community service every year - a month in the spring and a month in the fall." In just a year, Khoshutovo has changed. Under the guidance of the “sand teacher”, the only plant that grows well on these soils — a shrub hell-like willow tree — was planted everywhere.

Strips of the shelves strengthened the sands, protected the village from desert winds, increased the yield of herbs and allowed to irrigate the gardens. Now the residents were drowning stoves with shrubs, and not with smelly dry manure, from their branches they began to weave baskets and even furniture, which gave an additional income.

A little later, Naryshkina took out pine seedlings and planted two planting strips that protected the crops even better than the bush.Not only children but also adults began to go to Maria Nikiforovna’s school, learning the “wisdom of life in the sandy steppe”.

In the third year, a disaster happened in the village. Every fifteen years, nomads passed through the village “along their nomadic ring” and collected what the rested steppe had generated.

At that time, the windless steppe was smoking on the horizon: then thousands of nomad horses rode and their herds stamped.

Three days later, nothing remained of the three-year labor of the peasants - all the nomads' horses and cattle were destroyed and trampled, and people scooped up wells to the bottom.

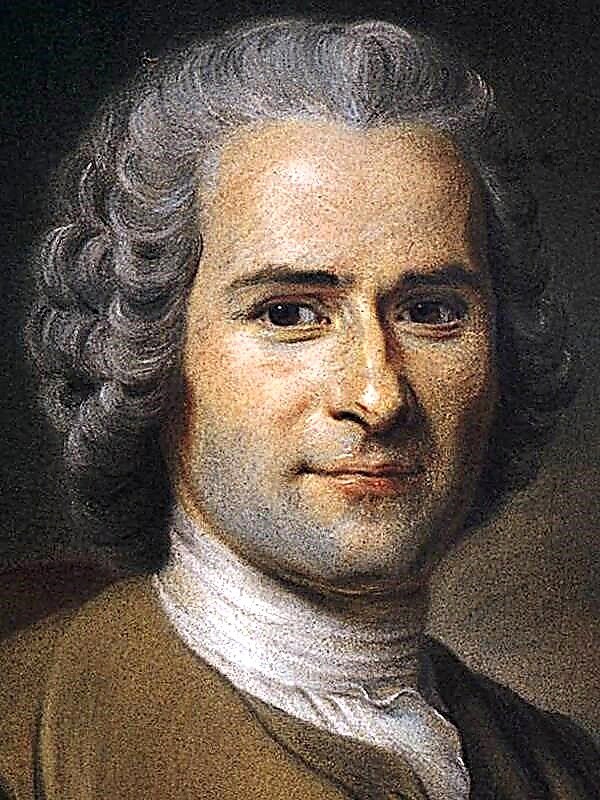

The young teacher went to the leader of the nomads. He silently and politely listened to her and replied that the nomads were not evil, but "there is little grass, a lot of people and livestock." If there are more people in Khoshutovo, they will drive the nomads "to the steppe to death, and this will be as fair as it is now."

He who is hungry and eats the grass of his homeland is not a criminal.

Secretly appreciating the leader’s wisdom, Naryshkina went to the district with a detailed report, but she was told there that Khoshutovo would now do without her. The population already knows how to deal with sand and, after the nomads leave, will be able to further revitalize the desert.

The manager suggested that Maria Nikiforovna transfer to Safuta, a village inhabited by nomads who switched to a settled lifestyle, in order to teach local residents the science of survival among the sands. By teaching the inhabitants of Safuta "sand culture", you can improve their lives and attract the rest of the nomads, who will also settle and stop exterminating the plantings around Russian villages.

The teacher was sorry to spend her youth in such a remote place, having buried her dreams of a life partner, but she remembered the hopeless fate of the two peoples and agreed. At parting, Naryshkina promised to come in fifty years, but not along the sand, but along a forest road.

Saying goodbye to Naryshkina, the astonished head said that she could manage not a school, but a whole nation. He felt sorry for the girl and for some reason was ashamed, “but the desert is the future world,‹ ... ›and people will be noble when a tree grows in the desert”.