The article is devoted to the drama Ostrovsky "Thunderstorm". At the beginning of her Dobrolyubov writes that "Ostrovsky has a deep understanding of Russian life." He then analyzes the articles on Ostrovsky by other critics, writes that they "lack a direct view of things."

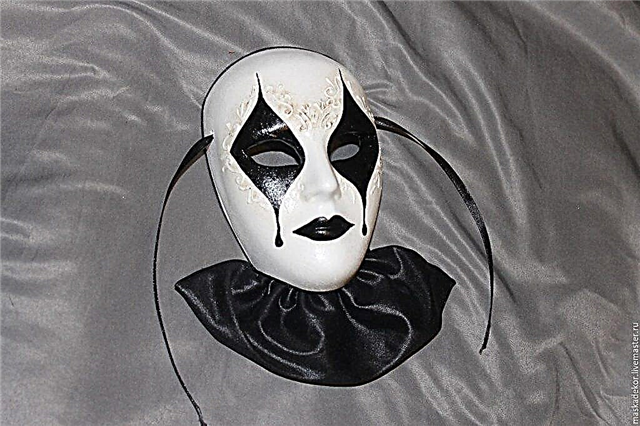

Then Dobrolyubov compares Thunderstorm with dramatic canons: “The subject of the drama should certainly be an event where we see the struggle of passion and debt - with the unfortunate consequences of the victory of passion or with the happy when debt overcomes.” There should also be unity of action in the drama, and it should be written in a high literary language. “Thunderstorm” at the same time “does not satisfy the most essential goal of the drama - to inspire respect for moral duty and to show the disastrous consequences of passion for passion. Katerina, this criminal, seems to us in the drama not only not in a rather gloomy light, but even with the radiance of martyrdom. She speaks so well, suffers so pitifully, everything around her is so bad that you arm yourself against her oppressors and, thus, in her face you justify the vice. Consequently, the drama does not fulfill its high purpose. The whole action is sluggish and slow, because it is cluttered with scenes and faces that are completely unnecessary. Finally, the language spoken by the characters surpasses all patience of a well-mannered person. ”

This comparison with the canon Dobrolyubov conducts in order to show that an approach to a work with a ready-made idea of what should be shown in it does not give a true understanding. “What to think of a man who, at the sight of a pretty woman, suddenly begins to resonate that her camp is not the same as that of Venus de Milo? The truth is not in the dialectical subtleties, but in the living truth of what you are reasoning about. You can’t say that people were evil by nature, and therefore one cannot accept principles for literary works such as, for example, vice always triumphs, and virtue is punished. ”

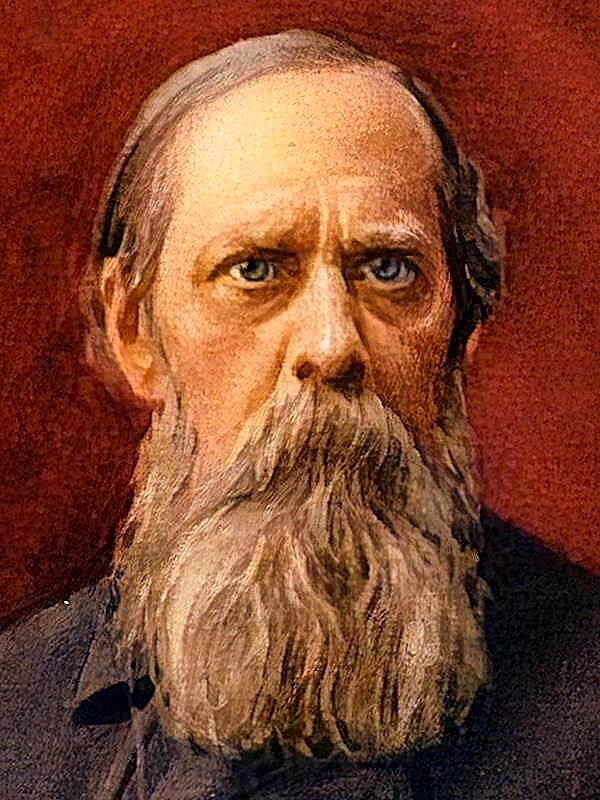

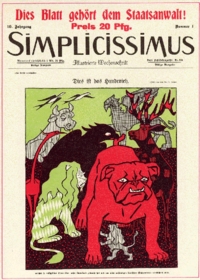

“The literator has so far been given a small role in this movement of mankind towards the natural beginnings,” Dobrolubov writes, after which he recalls Shakespeare, who “moved the general consciousness of people by several steps that no one had ascended to.” Further, the author turns to other critical articles about the Storm, in particular, Apollo Grigoriev, who claims that Ostrovsky’s main merit lies in his “nationality”. “But what the nationality consists of, Mr. Grigoryev does not explain, and therefore his remark seemed to us very amusing.”

Then Dobrolyubov comes to define Ostrovsky’s plays as a whole as “plays of life”: “We want to say that he always has the general environment of life in the foreground. He does not punish the villain or the victim. You see that their position dominates them, and you blame them only for not showing enough energy to get out of this position. And that's why we do not dare to consider those faces of Ostrovsky's plays that are not directly involved in the intrigue unnecessary and redundant. From our point of view, these persons are just as necessary for the play as the main ones: they show us the atmosphere in which the action takes place, draw a position that determines the meaning of the main characters of the play. ”

In "Thunderstorm" the need for "unnecessary" persons (secondary and episodic characters) is especially visible. Dobrolyubov analyzes the replicas of Feklushi, Glasha, Wild, Kudryash, Kuligin, etc. The author analyzes the internal state of the heroes of the "dark kingdom": "everything is somehow restless, not good for them.In addition to them, without asking them, another life grew up, with different principles, and although it is still not well visible, it already sends bad visions to the dark tyranny of tyrants. And Kabanova is very seriously upset by the future of the old order with which she has lived out a century. She foresees the end of them, tries to maintain their significance, but already feels that there is no previous respect for them and that they will be abandoned as soon as possible. ”

Then the author writes that “The Storm” is “Ostrovsky's most decisive work; the mutual relations of tyranny brought in it to the most tragic consequences; and for all that, the majority of those who read and saw this play agree that there is even something refreshing and encouraging in The Storm. This “something” is, in our opinion, the play's background, indicated by us and revealing the precariousness and near end of tyranny. Then the very character of Katerina, drawn against this background, also blows on us with a new life that opens to us in her very death. ”

Further, Dobrolyubov analyzes the image of Katerina, perceiving it as “a step forward in all our literature”: “Russian life has reached the point that there was a need for more active and energetic people.” The image of Katerina “is steadfastly faithful to her sense of natural truth and selfless in the sense that he is better off in death than life under those principles that are contrary to him. In this wholeness and harmony of character lies its strength. Free air and light, contrary to all the precautions of dying tyranny, burst into Katerina’s cell, she is eager for a new life, even if she had to die in this outburst. What is her death? Anyway, she does not consider life the vegetation that fell to her in the Kabanov family. ”

The author analyzes in detail the motives of Katerina’s actions: “Katerina does not belong at all to violent characters, unhappy, loving to destroy. On the contrary, this character is predominantly creative, loving, ideal. That is why she tries to ennoble everything in her imagination. The feeling of love for a man, the need for gentle pleasures naturally opened up in a young woman. ” But it will not be Tikhon Kabanov, who is “too clogged to understand the nature of Katerina’s emotions:“ I won’t understand you, Katya, ”he tells her,“ you won’t get a word from you, not just affection, but it’s so you climb. " So usually spoiled natures judge a strong and fresh nature. ”

Dobrolyubov comes to the conclusion that in the image of Katerina, Ostrovsky embodied a great popular idea: “In other works of our literature, strong characters resemble fountains that depend on an extraneous mechanism. Katerina is like a big river: a flat bottom, good - it flows calmly, large stones met - it jumps over them, a precipice - cascades, damn it - it rages and erupts elsewhere. Not because she is seething so that the water suddenly wants to make noise or become angry at obstacles, but simply because she needs it to fulfill her natural requirements - for the further course. ”

Analyzing the actions of Katerina, the author writes that he considers the escape of Katerina and Boris possible as the best solution. Katerina is ready to run, but another problem comes up here - the material dependence of Boris on his uncle Wild. “We said above a few words about Tikhon; Boris is the same, in essence, only educated. ”

At the end of the play, “We are pleased to see Katerina’s deliverance - even though through death, if it cannot be otherwise. Living in the dark realm is worse than death. Tikhon, rushing to the body of his wife, pulled out of the water, shouts in self-forgetfulness: “It’s good for you, Katya! But why did I stay to live in the world and suffer! “With this exclamation the play ends, and it seems to us that nothing could have been thought up stronger and more truthful than such an ending. Tikhon’s words make the viewer think not of a love affair, but of this whole life, where the living envy the dead. ”

In conclusion, Dobrolyubov addresses the readers of the article: “If our readers find that Russian life and Russian power are called out by the artist in Thunderstorm to a decisive cause, and if they feel the legitimacy and importance of this matter, then we are happy no matter what our scientists say and literary judges. "