Events take place in July, in Lucerne, one of the most romantic cities in Switzerland. Travelers of all nations, and especially the British, have an abyss in Lucerne. The city is adapted to their tastes: the old houses are broken, on the site of the old bridge they made a straight embankment like a stick. It may be that these embankments, and houses, and sticky, and the British are very good somewhere - but not here, among this strangely majestic and at the same time inexpressibly harmonious and soft nature.

Prince Nekhlyudov was captivated by the beauty of the nature of Lucerne, under its influence he felt inner uneasiness and the need to express somehow an excess of something that suddenly overwhelmed his soul. He's talking ...

“... It was the seventh hour of the evening. Amidst the splendor of nature, complete harmony in front of my window, a white stick of the embankment stuck foolishly, sticky with props and green benches - poor, vulgar human works, not drowned like distant summer cottages and ruins, in the general harmony of beauty, but, on the contrary rudely contradicting her. I involuntarily tried to find a point of view from which I could not see it, and, in the end, I learned to look like this.

Then they called me to dinner. Two tables were set in the magnificent hall. Behind them reigned English severity, decency, uncommunicativeness, based not on pride, but on the absence of the need for rapprochement, and lonely contentment in the convenient and pleasant satisfaction of their needs. No excitement was reflected in the movements of the diners.

At such dinners, it always becomes hard, unpleasant, and finally sad. It all seems to me that I am punished, as in childhood. I tried to rebel against this feeling, I tried to speak with my neighbors; but, apart from phrases which, obviously, were repeated a hundred thousandth time in the same place and with the same face, I received no other answers. Why, I asked myself, why do they deprive themselves of one of the best pleasures of life, enjoyment with each other, enjoyment of man?

Whether it happened in our Parisian guesthouse, where we, twenty people of the most diverse nations, professions and characters, under the influence of French sociability, came to a common table, as if for fun. And after lunch, we pushed aside the table and, to the beat, not to the beat, began to dance until the evening. There we were, although flirty, not very smart and respectable people, but we were people.

I felt sad, as always after such dinners, and, not having finished the dessert, in the most gloomy mood, I went to hang around the city. The dull, dirty streets of the city further intensified my longing. It was already completely dark in the streets, when I, without looking around myself, without any thought in my head, went to the house, hoping to get rid of my gloomy mood of sleep.

So I walked along the promenade to Schweizerhof (the hotel where I lived), when suddenly I was struck by the sounds of strange but extremely pleasant music. These sounds instantly life-giving effect on me. It was as if a bright light had penetrated my soul, and the beauty of the night and the lake, to which I had previously been indifferent, suddenly struck me with joy.

Directly in front of me, in a twilight in the middle of the street, in a semicircle, a shy crowd of people, and in front of the crowd, at some distance, a tiny man in black clothes. Guitar chords and several voices floated in the air, which, interrupting each other, did not sing the theme, and in some places, singing the most prominent places, made it feel. It was not a song, but a light sketch of a song in the workshop.

I could not understand what it was; but it was beautiful. All the confused impressions of life suddenly got meaning and charm for me.Instead of the fatigue, indifference to everything in the world that I felt a minute before, I suddenly felt the need for love, hope and the causeless joy of life.

I came closer. The little man was a wandering Tyrolean. There was nothing artistic in his clothes, but the dashing, childishly cheerful pose and movements with his tiny growth made a touching and at the same time amusing sight. I immediately felt fondness for this man and gratitude for the coup he made in me.

There was a noble public in the porch, windows and balconies of the magnificently lit Schweitzerhof, graceful waiters walking in the semicircle of the crowd. Everyone seemed to experience the same feeling that I had.

The singer’s small voice was extremely pleasant, but the tenderness, taste and sense of proportion with which he possessed this voice were unusual and showed him a great natural talent.

I asked one aristocratic footman who this singer is, how often he comes here. The footman replied that in the summer two times he came that he was a mendicant singer from Argovia.

At this time, the little man finished the first song, took off his cap and approached the hotel. Throwing his head back, he turned to the gentlemen standing at the windows and on the balconies, was silent for a little while; but since no one gave him anything, he threw up his guitar again. Upstairs, the audience was silent, but continued to wait for the next song, downstairs in the crowd they laughed at the fact that he expressed himself so strangely and that they hadn’t been given anything.

I gave him a few centimes. He began to sing again. This song, which he left for conclusion, was even better than all the previous ones, and from all sides in the crowd there were sounds of approval.

The singer again took off his cap, put it forward, two steps closer to the windows, but in his voice and movements I now noticed some indecision and childish timidity. The elegant audience still stood motionless. In the crowd below, loud voices and laughter were heard.

The singer repeated his phrase for the third time, but in a weaker voice, and did not even finish it and again extended his hand with a cap, but immediately dropped it. And the second time out of this hundred brilliantly dressed people who listened to him, not one left him pennies. The crowd burst out mercilessly.

The little singer said goodbye and put on his cap. The crowd gagged. On the boulevard, walking again resumed. Silent while singing, the street came to life again, only a few people, not approaching him, looked from a distance at the singer and laughed. I heard the little man say something under his breath, turned and, as if becoming even smaller, took quick steps to the city. The merry revelers who looked at him, still at some distance followed him and laughed ...

I was completely at a loss, it hurt and, most importantly, I am ashamed of a small man, of the crowd, of myself, as if I asked for money, they did not give me anything and laughed at me. Without looking back either, with a pinched heart, I quickly went to my house on the porch of Schweitzerhof.

At the magnificent, illuminated entrance, I met a courteous doorman and an English family. And to all of them, it seemed so easy, comfortable, clean and easy to live in the world, such in their movements and faces expressed indifference to any other people's lives and such confidence that the doorman would step aside and bow to them, and that, returning, they they will find a clean bed and rooms, and that all this should be, and that they have every right to all, that I suddenly unwittingly contrasted them with a wandering singer who, tired, maybe hungry, was now running away from the laughing crowd with shame.

Two times I walked back and forth past the Englishman, with inexpressible pleasure, pushing him with my elbow both times, and, going down the porch, ran in the dark towards the city where the little man had hidden.

He walked alone, with quick steps, no one came close to him, he seemed to mumble something angrily under his breath.I caught up with him and suggested that he go somewhere together to have a bottle of wine. He offered a “simple” cafe, and the word “simple” involuntarily led me to think not to go to a simple cafe, but to go to Schweitzerhof. Despite the fact that he, with timid excitement, several times refused Schweitzerhof, saying that it was too ceremonial there, I insisted.

The senior waiter Schweitzerhof, from whom I asked for a bottle of wine, listened seriously to me and, looking from head to toe the timid, small figure of the singer, strictly told the doorman to lead us into the hall to the left. The hall to the left was a drinking room for ordinary people.

The waiter, who came to serve us, looking at us with a mocking smile and putting his hands in his pockets, was talking about something with a humpback dishwasher. Apparently, he tried to let us notice that he felt infinitely superior to the singer by his social position.

“Champagne, and the best,” I said, trying to take on the most proud and majestic look. But neither champagne nor my appearance affected the lackey. He slowly left the room and soon returned with wine and two more footmen. All three smiled ambiguously, only the hunchbacked dishwasher seemed to be watching us with participation.

In the fire, I considered the singer better. He was a tiny, wiry man, almost a dwarf, with bristly black hair, always crying with large black eyes, devoid of eyelashes, and an extremely pleasant, sweetly folded mouth. Clothing was the simplest and poorest. He was unclean, tattered, tanned, and generally had the appearance of a working man. He looked more like a poor merchant than an artist. Only in constantly moist, shiny eyes and collected mouth was something original and touching. In appearance he could be given from twenty-five to forty years; indeed he was thirty-eight.

The singer spoke about his life. He comes from Argovia. In childhood, he also lost his father and mother, he has no other relatives. He never had a fortune. He studied carpentry, but twenty-two years ago he became caries in his hand, depriving him of the opportunity to work. From childhood he had a desire for stumps and began to sing. Foreigners occasionally gave him money. He made a profession out of this, bought a guitar, and now he has been wandering around Switzerland and Italy for eighteen years, singing in front of hotels. All his luggage is a guitar and a wallet, in which he now had only one and a half francs. Every year, eighteen times, it goes through all the best, most visited places in Switzerland. Now it’s hard for him to walk, because from a cold the pain in his legs worsens every year, and his eyes and voice become weaker. Despite this, he is now leaving for Italy, which he especially loves; in general, as it seems, he is very pleased with his life. When I asked him why he was returning home, whether he had relatives there, or a house and land, he replied:

- There is nothing, otherwise I would have started walking like that. But I’m coming home, because somehow I’m somehow drawn to my homeland.

I noticed that wandering singers, acrobats, magicians like to call themselves artists, and therefore several times hinted to his interlocutor that he was an artist, but he did not recognize this quality at all, but looked quite simply as a means of living, to your own business. When I asked him if he himself composed the songs he sings, he was surprised at such a question and replied that where to him, these are all old Tyrolean songs.

We are crazy about the artists' health; he drank half a glass and found it necessary to think and thoughtfully lead his eyebrows.

- For a long time I did not drink such wine! In Italy, wine is good, but it is even better. Ah, Italy! nice to be there!

“Yes, they can appreciate music and artists there,” I said, wanting to bring him to an evening failure in front of Schweitzerhof.

“No,” he answered, “Italians are musicians themselves, which are not in the whole world; but I'm only about tyrolean songs. This is still news to them.

“Well, gentlemen are there more generously?” I continued, wanting to force him to share my anger into the inhabitants of Schweitzerhof.

But the singer did not think to resent them; on the contrary, in my remark he saw a rebuke to his talent, which did not cause a reward, and tried to justify himself in front of me.

- There are a lot of harassment from the police. Here, according to the laws of the republic, they are not allowed to sing, but in Italy you can walk as much as you want, no one will say a word. Here, if they want to allow it, they will allow it, but do not want it, they can put them in jail. And what am I singing, so am I doing harm to anyone? What is this? rich can live as they want, but someone like me can’t even live. What kind of laws are these? If so, then we do not want a republic, but we want ... we just want ... we want ... - he hesitated a little, - we want natural laws.

I poured him another glass.

“I know what you want,” he said, squinting his eyes and shaking a finger at me, “you want to get me drunk, see what will come of me, but no, you won’t succeed ...”

So we continued to drink and talk with the singer, and the footmen continued, unashamedly, to admire us and, it seems, to make fun of. Despite the interest in my conversation, I could not help noticing them and became angry more and more. I already had a ready supply of anger at the inhabitants of Schweitzerhof, and now this lackey public was tempting me. The doorman, without removing his cap, entered the room and, leaning on the table, sat beside me. This last circumstance, hitting my vanity or vanity, finally blew me up and gave the outcome to the anger that had been gathering in me all evening.

I jumped up.

- What are you laughing at? I shouted at the footman, feeling my face turn pale. “What right do you have to laugh at this gentleman and sit next to him when he is a guest, and you are a footman?” Why didn’t you laugh at me this afternoon and sit next to me? Because he is poorly dressed and sings on the street? He is poor, but a thousand times better than you, I'm sure of that. Because he did not insult anyone, and you insult him.

“Yes, I’m nothing that you are,” my enemy footman shyly answered. “Am I stopping him from sitting.”

The footman did not understand me, and my German speech was in vain. The doorman stood up for the footman, but I attacked him so swiftly that the doorman pretended not to understand me either. A hunchbacked dishwasher, fearing a scandal, or sharing my opinion, took my side and, trying to stand between me and the doorman, persuaded him to remain silent, saying that I was right and asked me to calm down.

The singer represented the most miserable, frightened face and, apparently not understanding what I was getting excited about and what I wanted, asked me to leave as soon as possible from here. But anger flared up in me more and more. I remembered everything: the crowd that laughed at him, and the listeners who did not give him anything, I did not want to calm down for anything in the world.

- ... Here it is equality! You wouldn’t dare to bring the English to this room, the very British who listened for nothing to this gentleman, that is, they each stole several santims who should have given him. How dare you point this hall?

“The other room is locked,” the doorman answered.

Despite the admonitions of the hunchback and the singer’s request to go home better, I demanded the chief waiter to accompany me and the singer to that hall. Ober-waiter, hearing my angry voice, did not argue and with contemptuous courtesy said that I can go wherever I want.

The hall was open, lit, and on one of the tables sat an Englishman with a lady. Despite the fact that we were shown a special table, I sat down with the dirty singer to the Englishman himself and ordered here to give us an unfinished bottle.

The English at first, in surprise, then looked with embittance at the little man, who was neither alive nor dead, sat beside me, and went out. Behind the glass doors, I saw the Englishman say something angrily to the waiter, pointing his hand in our direction. I was happy to expect that they would come to lead us out and that it would finally be possible to pour all my indignation on them.But, fortunately, although it was unpleasant to me then, we were left alone.

The singer, who had previously refused wine, now hastily drank everything that was left in the bottle so that he could only get out of here as soon as possible. He told me the strangest, confusing phrase of thanks. But still, this phrase was very pleasant to me. We went out into the canopy with him. There were footmen and my enemy doorman. They all looked at me as insane. I let the little man catch up with this whole audience, and here, with all due respect, I took off my hat and shook his hand with a numb, withered finger. The lackeys pretended not to pay the slightest attention to me. Only one of them laughed with a sardonic laugh.

When the singer, bowing, hid in the dark, I went upstairs, but, feeling too excited for sleep, I again went outside to walk until I calm down, and I confess, moreover, in the vague in the hope that there would be a chance to cling to a doorman, footman or Englishman and prove to them all their cruelty and, most importantly, injustice. But, except for the doorman, who, having seen me, turned his back to me, I did not meet anyone and, one by one, began to walk back and forth along the promenade.

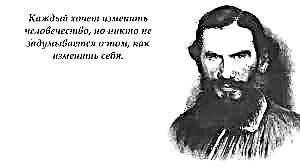

“Here it is, the strange fate of poetry,” I reasoned, calming down a bit. - Everyone loves her, they desire and seek her alone in life, and no one recognizes her strength, no one appreciates this best good of the world. Ask these inhabitants of Schweizerhof: what is the best good in the world? and everyone, taking a sardonic expression, will tell you that the best good is money. Why did you all pour out onto the balconies and listen in reverential silence to the song of the little beggar? Is it really the money that has collected you all on the balconies and made you stand silently and motionless? No! But it forces you to act, and will forever move stronger than all other engines of life, the need for poetry, which you do not recognize, but feel and will feel, until something human remains in you.

You admit love for the poetic only in children and silly young ladies, and then you laugh at them. Yes, children look sensibly at life, they love that which a person should love, and that which will bring happiness, and life has confused and corrupted you before, that you laugh at the fact that you love and look for what you hate and what makes your unhappiness.

But not this struck me the most this evening. I was struck by how you, children of a free, humane people, you Christians, to the pure pleasure that an unfortunate asking person brought you, answered with coldness and mockery! Of the hundreds of you, happy, rich, there was not one who would have thrown a coin to him! Shamed, he went away from you, and the crowd, laughing, pursued and insulted not you, but him, because you cold, cruel and dishonorable; for the fact that you stole from him the pleasure that he brought you, for this his insulted. "

This is an event that historians of our time should write in fiery letters. This event is more significant and has a deeper meaning than facts in newspapers and stories. This is not a fact for the history of human deeds, but for the history of progress and civilization.

Why do these people, in their chambers, rallies and societies, ardently caring about the state of celibate Chinese in India, about the spread of Christianity and education in Africa, about composing societies correcting all of humanity, do not find in their souls a simple primitive feeling of a person towards a person? Is it really that equality for which so much innocent blood was shed and so many crimes committed?

Civilization is good; barbarism is evil; freedom is good; bondage is evil. This imaginary knowledge destroys the instinctive, blissful primitive needs of the good in human nature. And who will determine to me that freedom, that despotism, that civilization, that barbarism? One, only one, we have an infallible leader, the Universal Spirit, penetrating us all together and everyone.And this one infallible voice drowns out the noisy, hasty development of civilization.

... At this time from the city in the dead silence of the night, I far, far heard the little man’s guitar and his voice. There he sits now somewhere on a dirty threshold, looks into the moonlit sky and sings joyfully in the middle of a fragrant night, in his soul there is neither reproach, nor malice, nor remorse. And who knows what is now being done in the soul of all these people, behind these rich walls? Who knows if they all have as much carefree, meek joy of life and harmony with the world, how much it lives in the soul of this little man? The infinite goodness and wisdom of the one who allowed all these contradictions to exist. Only to you, an insignificant worm, impudently trying to penetrate his laws, his intentions, only to you they seem to be contradictions. In your pride, you thought of breaking out of the laws of the general. No, and you with your little, vulgar indignation at lackeys, and you too answered the harmonious need of the eternal and infinite ...

Moby Dick

Moby Dick